Market equilibrium

Demand shows us the quantity demanded by consumers at various

prices.

Supply shows us the quantity supplied by the firms

at various prices.

However, demand by itself, or supply by itself cannot

tell us what the price will be in the market.

We can, however, answer this question by using demand

and supply together.

Market equilibrium (contd.)

The price that will eventually be realized in a market

is one at which quantity demanded equals quantity

supplied.

This price, \( p_{e} \) where quantity demanded equals quantity

supplied, is called the equilibrium price; and the

corresponding quantity is called the equilibrium

quantity.

The reason \( p_{e} \) is called the equilibrium price

is that when price equals \( p_{e} \), as long as there

is no change in the underlying conditions that affect

demand and supply, there is no upward or downward pressure

on price.

For any price other than \( p_{e} \) there is an upward

or downward pressure on price depending on whether price

is below \( p_{e} \) or above \( p_{e} \).

Market equilibrium: Graphical representation

Equilibrium price = $4.50

Equilibrium quantity = 300

Why is $6.00 not an equilibrium price?

Presence of surplus (quantity supplied > quantity demanded)

will cause a downward pressure on prices.

Sellers will reduce prices to sell more.

Why is $3.00 not an equilibrium price?

Presence of a shortage (quantity supplied < quantity demanded)

will cause an upward pressure on prices. Buyers will

offer more money and sellers will increase prices.

Solving for equilibrium price and quantity

(Chapter 4, Problem 1 of Acemoglu et al.)

What is the equilibrium price?

Example: Solve for equilibrium price and

quantity.

Suppose demand is given by:

$$

Q_{d} = 1000 - 200 P

$$

and, supply is given by:

$$

Q_{s} = 800 P

$$

where, \( Q \) is the quantity of oranges in a day and

\( P \) is the price per orange (measured in dollars).

Solve for the market equilibrium.

Applications of Market Equilibrium

Using the market equilibrium framework to understand

the effect of various events on prices and quantities.

Example 1: (Chapter 4, Problem 6 of Acemoglu et al.)

There is a sharp freeze in Florida that damages the orange

harvest.

1. How will this affect the price and quantity of oranges?

2. How will this affect the price and quantity of orange juice?

Example 2: (Chapter 4, Problem 5 of Acemoglu et al.)

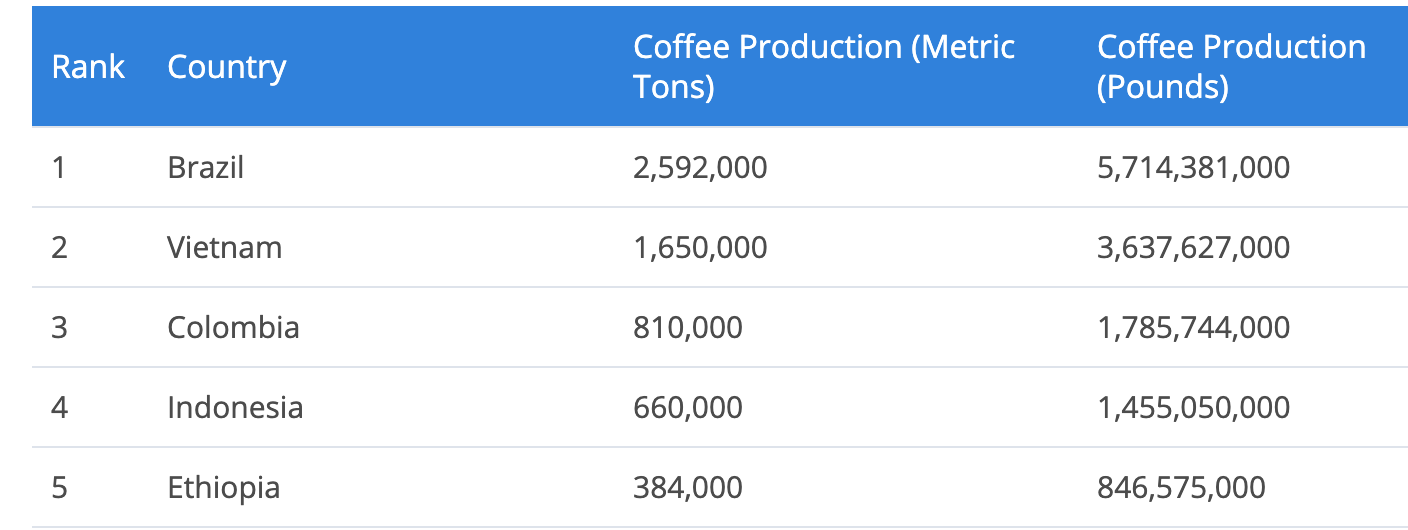

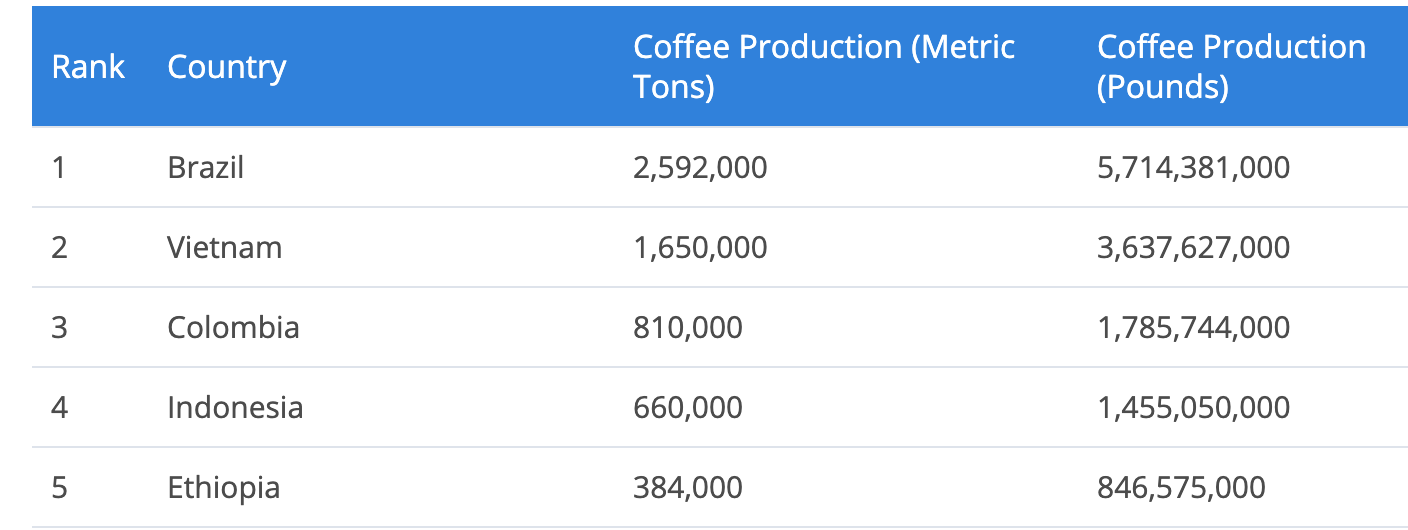

Brazil is the world's largest coffee producer.

(See

the article on worldatlas.com)

A severe drought in 2013-14 damaged Brazil's coffee crop. The price of

coffee beans doubled in the first three months of 2014.

How do you think this affected the equilibrium price and quantity of tea?

Example 3: (Chapter 4, Problem 8 of Acemoglu et al.)

Land in Sonoma, California can be used either to grow grapes for

Pinot Noir wine or to grow Gravenstein applies. If there is a permanent

rightward shift in demand for Pinor Noir, how will this affect

the equilibrium price and quantity of Gravenstein apples?

Example 4: (Chapter 4, Problem 3 of Acemoglu et al.)

Suppose that a pest attack on the tomato crop increases

the cost of producing ketchup. In addition, a mild winter

causes cattle herds to be unusually large, causing the

price of hamburgers to fall.

What will be the effect on equilibrium price and quantity

of ketchup? Assume that hamburgers and ketchup are

complements.

Effect of per-unit taxes and Tax Incidence

Suppose a per-unit tax is to be imposed in a market. It can be

imposed on the buyers, or on the sellers. How will the

two parties be affected in each case?

Are the buyers better off when the tax is imposed on the

sellers instead of the buyers?

Are the sellers better off when the tax is imposed on

the buyers instead of the sellers?

By using our model of the market we shall see that

the effect on buyers and sellers does not depend on whom

(sellers or the buyers) the tax is imposed.

Original equilibrium

Equilibrium price = $3.50.

Equilibrium quantity = 350 units

Tax on buyers of $1 per unit

Equilibrium before tax:

price = $3.50, quantity = 350.

Equilibrium after tax:

price = $3.00, quantity = 300.

Amount paid by the consumer:

$3.00 + $1.00 = $4.00.

Amount received by the seller:

$3.00.

Tax on sellers of $1 per unit

Equilibrium before tax:

price = $3.50, quantity = 350.

Equilibrium after tax:

price = $4.00, quantity = 300.

Amount paid by the consumer:

$4.00.

Amount received by the seller:

$4.00 - $1.00 = $3.00

Welfare effects of taxes

Before we can study the welfare effects, we need to know

how we can measure welfare.

A commonly used approach in Economics is to define

Welfare/Social Surplus as:

Consumer surplus (CS)

+ Producer surplus (PS)

+ (Government Revenue - Government Expenditure)

+ (Externality benefits - Externality Costs)

We have not yet discussed the notion of externality, and

you can ignore it for now. We will talk about it after a few

classes.

Welfare effects of taxes (continued)

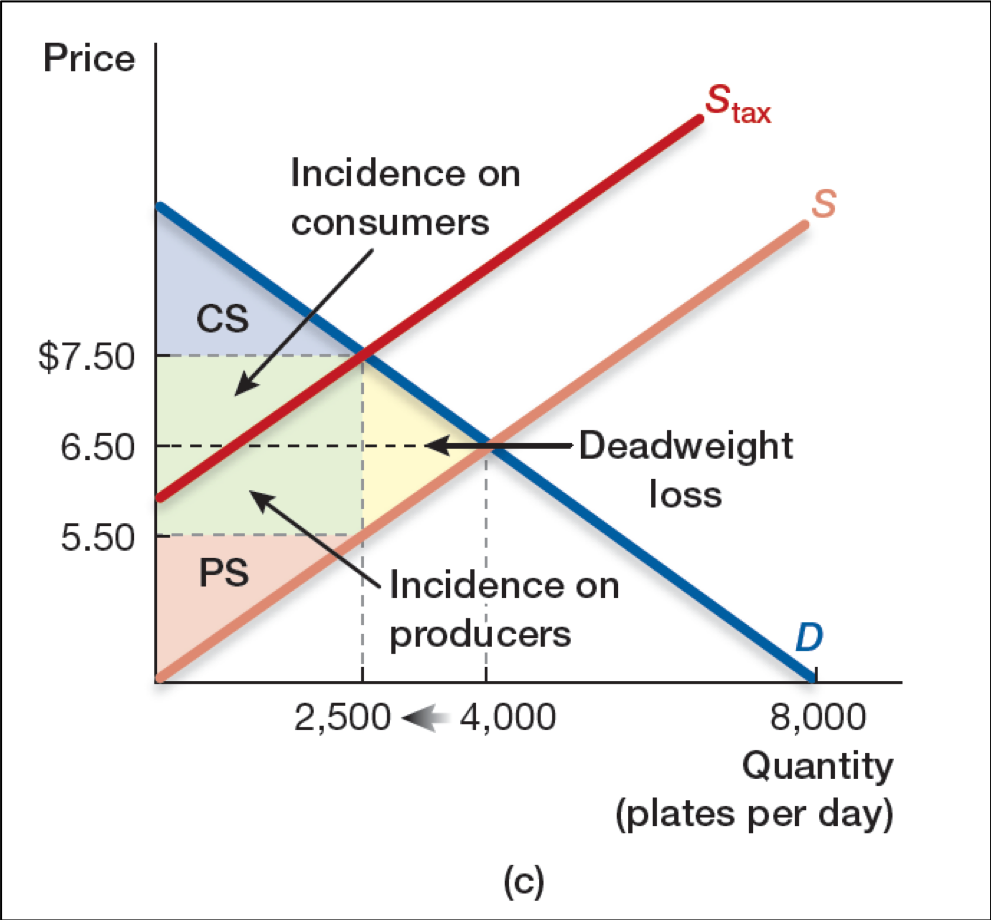

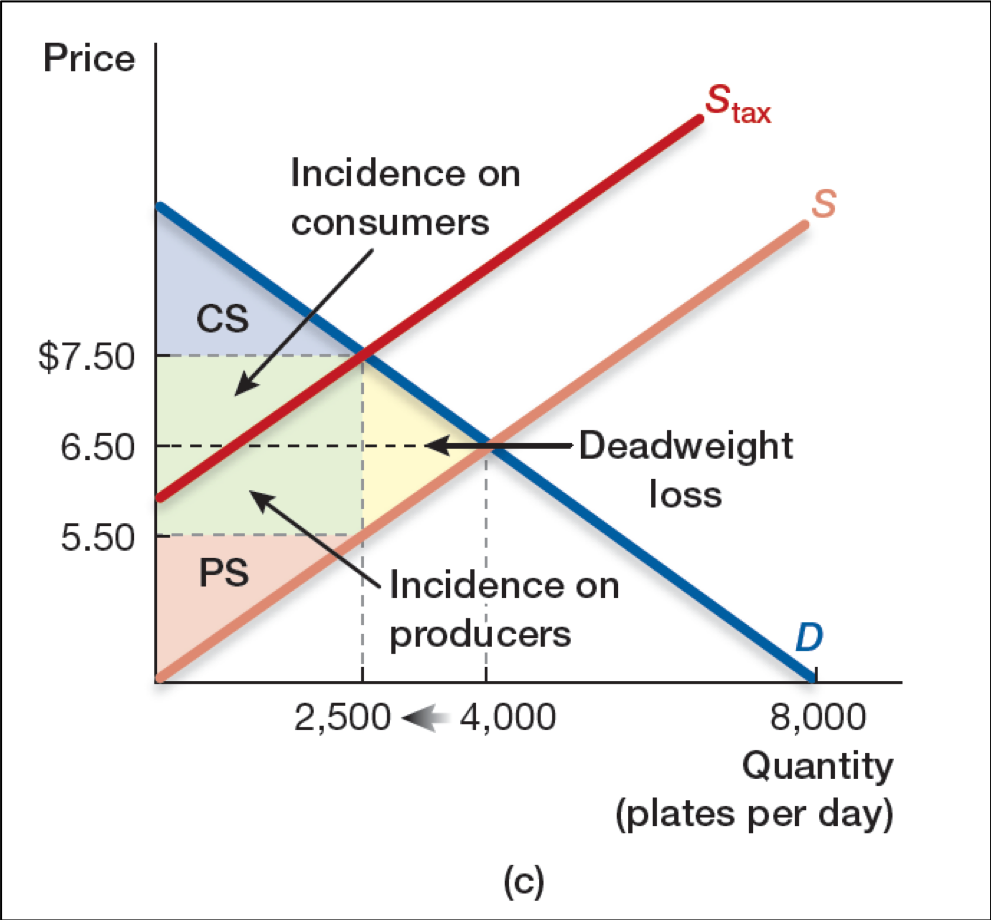

The figure to the left shows the effect of a tax on sellers.

Identify the welfare effects of this tax using the labeled areas.

Consumer surplus before tax:

1 + 2 + 3 + 4

Consumer surplus after tax:

1

Hence, change in consumer surplus:

- 2 - 3 - 4.

Welfare effects of taxes (continued)

Producer surplus before tax:

5 + 6 + 7

Producer surplus after tax:

2 + 5

Hence, change in producer surplus:

2 - 6 - 7

Welfare effects of taxes (continued)

Government Revenue before tax

None.

Government Revenue after tax:

3 + 6

Hence, Change in Goverment Revenue

3 + 6

Welfare effects of taxes (continued)

Putting changes in consumer surplus, producer surplus, and

government revenue together, we obtain

Change in Welfare

= - 2 - 3 - 4 + 2 - 6 - 7 + 3 + 6

= - 4 - 7

Welfare effects of taxes (continued)

The

yellow highlighted

area (4 + 7) is the welfare loss due to taxes.

This loss is referred to as the

deadweight loss due to taxes.

Calculate the numerical values of changes in CS, PS

Tax Revenue and Welfare

Further practice

For practice with change in equilibrium outcome read chapter 4

and problems at the end of Chapter 4.

For the welfare effect of taxes find the changes in CS, PS, Tax Revenue

and Welfare in the following figure.

Demand and Supply responsiveness and Tax incidence

We know that how the tax burden is shared between buyers and sellers

does not depend on whether the tax is imposed on sellers or on buyers.

But, how is the burden shared? Is it shared equally?

Is most of it borne by the sellers, or by buyers?

What determines how the burden is shared?

How the tax burden is shared between buyers and sellers

depends on how responsive the quantity demanded and supplied are

to prices.

For example, consider necessities: products that people consume

because they need them, as opposed to because they provide

pleasure/entertainment. Bypass surgery is one example.

Next few slides illustrate how the burden shared depends on

demand responsiveness given the responsiveness of supply.

Demand responsiveness and the sharing of tax burden

(Demand 1)

The figure to the left shows the supply before tax (\(S_{0}\))

and the supply after tax (\( S_{1} \)).

What is the tax per unit? How

much of it is paid by the consumer, and how much is paid by the seller?

Tax per unit = $20.

Eqm. price before tax = $60.

Eqm. price after tax = $70.

Consumer's share of the burden per unit = $70 - $60 = $10.

Seller's share of the burden per unit = $20 - $10 = $10.

Consumer's share 50% of the tax burden.

Demand responsiveness and the sharing of tax burden

(Demand 2)

The figure to the left shows the supply before tax (\(S_{0}\))

and the supply after tax (\( S_{1} \)).

What is the tax per unit? How

much of it is paid by the consumer, and how much is paid by the seller?

Tax per unit = $20.

Eqm. price before tax = $60.

Eqm. price after tax = $75.

Consumer's share of the burden per unit = $75 - $60 = $15.

Seller's share of the burden per unit = $20 - $15 = $5.

Consumer's share 75% of the tax burden.

Demand responsiveness and the sharing of tax burden

(Demands 1 and 2)

Summary: Demand 2 is less responsive than Demand 1. Hence,

sellers pass on relatively greater burden of the tax

(75% instead of 50%) on consumers.

Effect of a price ceiling (A)

What is the welfare consequence of a price ceiling

at \(p_{ceilA}\)?

There is a welfare loss denoted by area

\(ABE\).

Effect of a price ceiling (B)

What is the welfare consequence of a price ceiling

at \(p_{ceilB}\)?

A price ceiling above the equilibrium price

has no welfare consequence. Market price will be

the same regardless of whether or not there is a ceiling.

Effect of a price floor (B)

What is the welfare consequence of a price floor

at \(p_{floorB}\)?

There is a welfare loss denoted by area

\(ABE\).

Effect of a price floor (A)

What is the welfare consequence of a price floor

at \(p_{floorA}\)?

A price floor below the equilibrium price

has no welfare consequence. Market price will be

the same regardless of whether or not there is a

price floor.